There have always been a handful of people playing the tune to which we all dance. Democracy was supposed to make a dent in that. After the system of feudal overlords and Kings which still exists in many parts of the world, there were very rich people who decided how culture moved and money was spent. The ghosts of America’s Gilded Age with its Vanederbilts and Rockerfellers still haunt our institutions and our streets. Then showing off became a bit crass, and the ultra- rich worked a little bit more in the shadows, and their names weren’t known to everyone.

Now, once again, we all know who the big players are, and even what they’re interested in, as they carve out the direction of not only culture, but human development and science, using their unimaginable resources like rivers through canyons. And we don’t seem to mind. Too much.

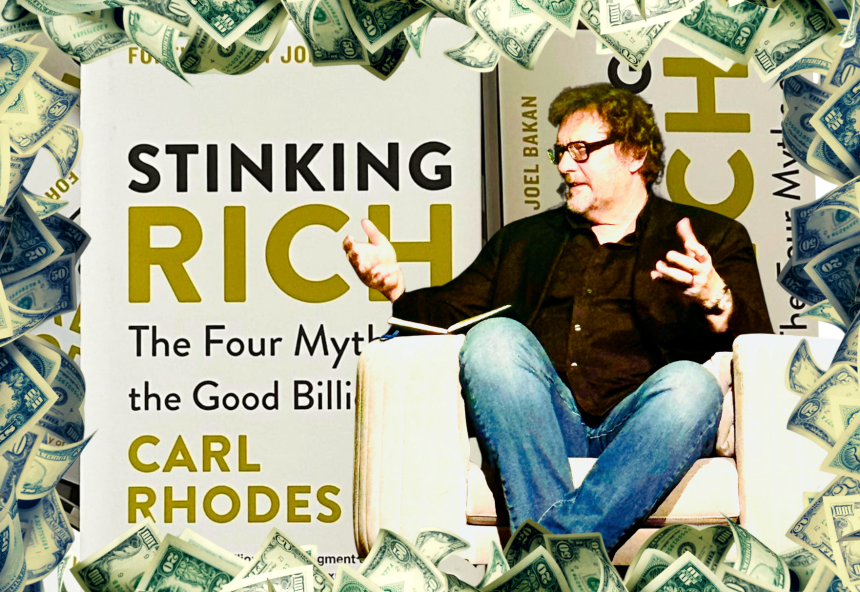

Carl Rhodes has written Stinking Rich to try and wake us from our fever dream, to pull back the curtain and force us to ask ourselves why we are so enamoured with these overlords, even as the living conditions for most of society become worse.

He’s tackling culture first, and even how we psychologically relate to the billionaire class. He has found four myths that are deep in the collective psyche which need tackling, and together become a false ‘force for good.’ The ‘heroic billionaire,’ the ‘generous billionaire,’ the ‘meritorious billionaire,’ and the ‘vigilante billionaire’ are all ripped apart, with a good dose of history and enough easy communication to get us all going.

Now the revolution is ready to move on to the next stage, Carl was ready for his Irresistible interview. We chatted about economics and policy and protest, and of course, music. Carl was generous enough to tell us about his favourite tunes and give us his ideal playlist to eat the rich to, which you’ll find at the end.

Rhodes is Professor of Organization Studies at the University of Technology Sydney. He studies the ethical and democratic dimensions of business, the economy and work. He is author of the bestselling Woke Capitalism (Bristol University Press, 2021) and a frequent commentator for the press.

Although we at Irresistible are probably unlikely to become billionaires, we do know that lots of billionaires read Irresistible, and so then, this also is for them.

How are you feeling about the book’s journey so far?

I think the timing was pretty good. Believe it or not, completely by coincidence, the official release date of the book was the day after Trump’s inauguration. I had no idea what was going to happen in the US with Trump and the coterie of billionaires. The book became more relevant than it might otherwise have been. The response has been really positive.

So much of what we’re dealing with now, in terms of economic and systemic injustices, seems to still hark back to the political and culture clashes of the 70s and 80s. How do you see that?

There’s always been rich people, but this particular variety of rich people was definitely seeded in the 80s. I went to the University of Cardiff from ’84 to ’87. That was the time when Margaret Thatcher was closing down all the mines, Ronald Reagan was in the White House, and there was a pivotal change in international politics, particularly as it relates to the economy and what people call neoliberalism. I think what we have now is those ideas extrapolated to some crazy extreme, beyond the imagining of that time

It was all text book free-market economics back then?

It was about deregulation, and talk about how capitalism and globalisation was going to set everyone free and change the world for the better. It was trickle-down economics; free the people at the top and everyone else will benefit. It’s just been a huge scam. I think part of the reason for writing this book is that, while there’s a lot written about economic inequality, I particularly wanted to dig around in the cultural dimensions of inequality. The inequalities are rife; between generations, between genders, North and South. These ultra-rich really represent all of that in such an extreme and vulgar form. How the hell did they get away with it?

A lot of economic theory rests on the fundamental idea of people acting in their best interests, and yet by voting in and supporting these kinds of models, we’re collectively not doing that?

It could be kind of a prisoner’s dilemma. Everyone acts based on what they think will benefit them, and the idea that everyone’s going to act somehow in concert for a collective best interest is a kind of democratic ideal. At the moment, we continue to act not in our collective best interests. But there is hope. Peter Dutton just lost the Australian election largely as a rejection of US style politics. However, individualism has largely replaced solidarity in community as a kind of value, at least in many Western societies. We think of self-interest as individual self-interest, rather than as collective self-interest. If everyone is pursuing individual self-interest, then certain people get a big share of the reward, and prosperity is very unevenly distributed. Nobody asks anymore what does it mean to have a fair society? It seems a question that is now quaint, and that needs to change.

With such wealth and power held by so few, it can feel like we’re slipping back into a version of a feudal or absolute monarchist system. Do you think that is actually how society has always been run, and we’ve lived through a blip after the World Wars of the 20th Century?

Its only since the Industrial Revolution that the means of production have existed to create this new kind of wealth, but if we go back to ancient Greek democracy, that original collectivity was only for certain types of people, and it didn’t include women. There’s a lot of slavery in old societies.

What we saw after the wars was a welfare state, particularly in Britain, built on the fear of the fascism that had just trampled through Europe. Now, if you look at the politics in the US it has fallen to some of those same problems, at least a quite radical form of populism.

Economic interests have taken over over social and political ones, and there has always been the tendency for some people to want to take a greater share of the world’s wealth than they should, but whether the last few decades have been a blip – I don’t know – you might be right – but I’m going to choose to believe that we don’t need to go backwards.

You talk about ‘Davos man’ in the book and that phrase is about a certain kind of global elite that has forged some of our current culture but has also somewhat faded. Its also obviously a very masculine term. What do you think about the kind of masculinity that is playing out in the power and cultural elites at the moment?

Firstly, the vast majority of billionaires are actually men. Notwithstanding that, the billionaires at the moment seem to reflect a particularly limited notion of what masculinity is, and I think it’s getting worse. You might have heard Mark Zuckerberg earlier this year talking about how he thinks business needs to be informed by more “masculine energy.” The ideas that dominate now are about individual control and wanting to be seen as the smartest person in the room, which is actually a bit of a shift from Davos masculinity. I think masculinity is headed in a troubling direction and Andrew Tate, Jordan Peterson and Joe Rogan are all signs of this.

What is it these guys want do you think?

Nobody needs a billion dollars, it’s an unfathomable amount of money. For these guys It’s about power. It’s about insecure men wanting to be the biggest cock on the block. and it’s just stupid. Bill Gates was once the richest man in the world, and now he thinks he can solve the pandemic and all the health problems of the world. Agencies like the World Health Organisation skew what they do to keep him happy. It’s a terrible role model for young men. There are many more ways to be a man, rather than simply needing power and control to mask weakness.

Inherent in their thinking seems to be the zero-sum game. One person has to take everything, and everyone else has to lose.

I write about this idea of meritocracy as a good thing, and I’m not so sure about that. If the people who are the most meritorious are the ones that rise to the highest positions of wealth and power, there’s a hidden side to that. It implies that if you and I haven’t risen to those heights, it’s our fault.

It’s because we’re losers and that we are not good enough, and so people deserve what they get. It ignores all the other factors that might be at play with success; race, gender, parents, education, country. That kind of competition seems rather harsh.

Do you think we need to find a more nuanced appreciation of competition?

There is a need for some inequality in society to motivate people to innovate and do better for themselves and their families. But it’s practical issue. The question is how much is it reasonable to have. Just because we live in a meritorious society, doesn’t mean that working people shouldn’t be able to afford to go to the dentist and put food on the table. Where’s the idea that we’re in this together, and prosperity is something to be shared, not hoarded by greedy, power-hungry money lovers.

People often use the original economic theories as an excuse for rampant hoarding, with phrases like ‘it’s just free market economics.’ The original texts didn’t encourage such inequalities however, and if anything were much more utilitarian. What do you think has been lost in modern interpretations of economics?

Adam Smith is often quoted from his book, The Wealth of Nations, which is a book against mercantilism – he would hate Donald Trump. He talks about how nations need to trade in order to build the wealth of each nation for everybody. His other famous book is The Theory of Moral Sentiments, which is really quite moralistic. In my book I talk about what he called the “vile maxim” which is the idea that rich people will only look after themselves and not care about anyone else. Anyone who justifies the current stage of affairs by using Adam Smith’s work is really misunderstanding it. As Alexander Pope said, “a little learning is a dangerous thing.”

Books like yours, and those by other economists like Thomas Piketty and Joseph Stiglitz, can reach new audiences with their popularity, outside of traditional economics readerships. Do you hope that these kinds of efforts can make real change?

I spent a lot of my career writing arcane academic articles that weren’t read by very many people and were probably largely unintelligible. Over the last 10 years I’ve started writing more for a general audience, and I think it’s really important that we’re thinking about these big problems and trying to get ideas out, so that they can inform public opinion and the democratic process.

Stiglitz is a Nobel Prize winner and obviously I’m not in his league, but he’s certainly a role model for me. Thomas Piketty, Robert Reich, and Naomi Klein are other writers I admire. The purpose of this kind of writing is to stimulate discussion and debate, and for people to think through the ideas they are being fed. If my writing even begins to have that kind of influence, then I’ve achieved my goals.

It’s about showing people that there are options?

In the book I quote the fiction writer Ursula K. Le Guin. She said, “We live in capitalism, its power seems inescapable – but then, so did the divine right of kings. Any human power can be resisted and changed by human beings.” Everything can be changed, but it requires a significant popular will and a democratic process for that to happen. Eventually, everything will change. Now we need to think about how can we collectively guide change in a way that benefits the most people.

Do you think there’s a bit of a chicken and egg situation with billionaires. They threaten democracy but that they come about more as democracy weakens?

I think the main threat that we see in liberal democratic countries now is populism. It’s effectively fascism. I think the rise of this populism and its connection to nationalism has largely been spawned by the kinds of inequalities that billionaires produce. Liberal democratic countries are a kind of uneasy marriage between capitalism and democracy. We often think of the economic as being separate from the political, but it’s hard to believe in democracy when you’re hungry, and that’s what inequality does- it diminishes the possibility of democracy. These billionaires represent a deeply anti- democratic situation, where you have a society that doesn’t aspire to talk about equal opportunities. I think there’s inequality first, and then the threat to democracy emerges from that.

Are there any new theorems you’re keen on?

The dutch philosopher Ingrid Robeyns has written a great book Limitarianism where she says that there should be a limit on wealth, that after a certain amount, extreme wealth is harmful and the rich should be told- “Well done, you’ve won capitalism! Yahoo! -Enjoy the spoils – But don’t try and take more than you can ever possibly need.”

Do you think in the end we need a new economic model?

I think there’s lots of things you can do now from a policy point of view. Changes can be made in the taxation system about progressive taxation and about wealth taxation. We could introduce a universal basic income. Education could be more equal, and childcare could be free. I think the problem we have is that we don’t have a political will to actually do these things. Even though these are economic problems, the solution’s must first be cultural. That’s often what we don’t look at. We’ve got to start being more pissed off about this – all of us together – instead of just accepting it.

What’s the first thing we should be pissed off about?

A few weeks ago in the Australian Financial Review there was the rich list. And then there was the ACSI review of the most highly paid CEOs. Where’s the outrage? Where’s the scandal? Where’s the taking to the street with pitchforks? One of the things that’s got to change first is the fact that we’re not repulsed by this greed. Then the policies are relatively straightforward.

The difference between the average pay in a company and that of the CEO has ballooned over the past few years. How does Australia compare to the rest of the world?

It’s not as bad in Australia as elsewhere. From the figures that were just released from the ASX 100, the CEO to average pay ratio is 55 to 1. In the 90s, it was about 17 to 1. In the past year we’ve gone from 50 to 55. Meanwhile, we’re having a whole debate about productivity, and business forums are saying that you can’t increase the minimum wage by more than $2 because you’re going to have productivity problem. When are these productivity matrices going to be applied to the remuneration of CEOs and billionaires. These conversations are not really productivity debates, they’re about how to maximise corporate profits and make inequality even worse.

There are massive productivity opportunities coming with technology and artificial intelligence, but who’s going to pocket the benefits? Let me tell you, it’s not going to be people on the minimum wage.

How do you see AI playing out in this space?

I suspect that it will make inequality worse and some people will lose their jobs. But it doesn’t have to be that way. Back in 1930, John Maynard Keynes released an article imagining that by 2030 people should be working a 15 hour week and be able to devote much of their lives to leisure and the pursuit of culture and so forth. He surmised that there are two things that will get in the way; war and inequality. Pretty much since then we’ve had war and inequality. Technology doesn’t have a conscience. It doesn’t have a morality. It’s how people use it that will make it good or bad.

What would you say to someone who feels inspired to start tackling these problems as a job? Which degree would you suggest young people take?

Everyone should always do the degree that they’re most interested in, not the one they think that will get them a good job, because it’s the one that you’re interested in that will actually get you a good job anyway. Nothing beats a good old-fashioned, undergraduate arts degree, I would certainly recommend that. For people who are younger again, people who are 15 or so, maybe still in school, I’d say read books. One thing I find interesting about young people is they talk a lot about radical communism. They’re referring to things people say in the media, but go and read Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels’ The Communist Manifesto. It’s not difficult. Read Rousseau’s The Social Contract and some other works in political philosophy. They can be massively eye- opening in so many ways. There’s such a wealth of ways for young people to open their minds.

What about everyone else – how can we all contribute to change?

I think we need to remember that different people have different abilities to influence the world. Obviously, a billionaire’s influence (and Irresistible Magazine’s) is huge, but we’re all citizens and we all have opportunities to use our voice, either occasionally at the ballot box, but also in how we interact with friends, family, and community. Someone might feel powerless, but we can all engage with the world – attend forums, go to public events, use the power of assembly, go on marches or join a protest. People can become citizen journalists, and they increasingly are. Even bringing up different topics around the water cooler at work will mean that politics is alive in the community. That’s what democracy is – a way of life as much as a political system. We’re all involved in that one way or another, and we all have opportunities to expand that kind of involvement, whoever we are in the world.