From the opening scenes, the cinematography of Holy Cow draws you into its world and creates a sense of a France that lingers in light and pastoral hush. Elio Balézeaux’s camera moves with summer’s inertia, letting milk‑stained tractors, pastures, and village markets speak in atmospheric depth. The shots are slow and beautiful, each frame reminding you when adolescence seemed to go on forever.

Holy Cow feels uniquely French, yet its core—teenagers testing their limits—is profoundly universal.

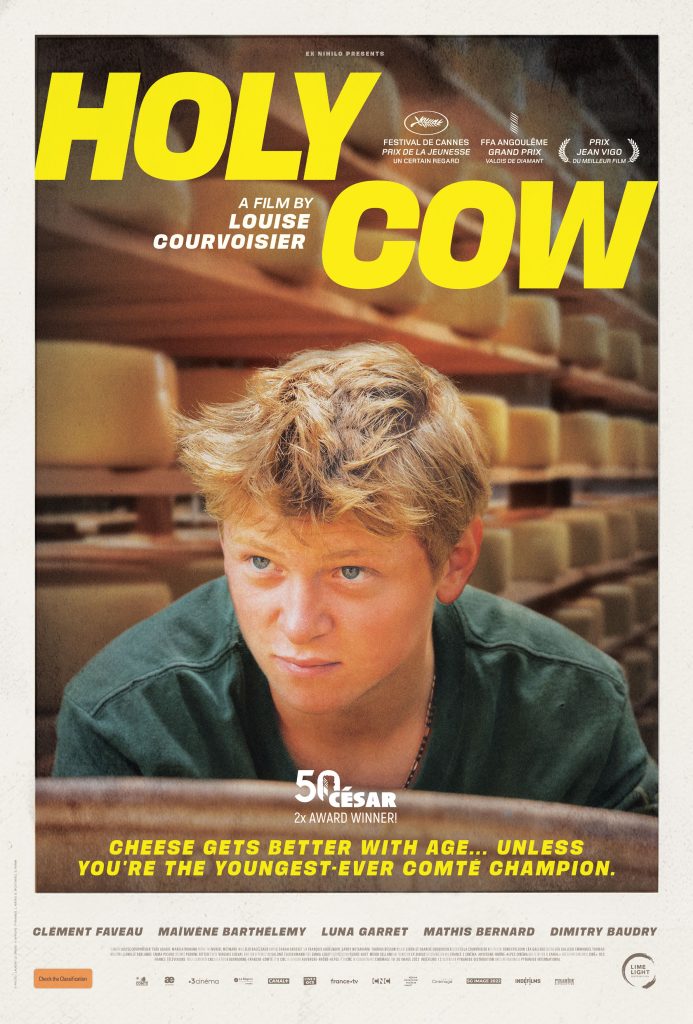

Totone, played with raw instinct by Clément Faveau, is the archetypal 18-year-old: reckless, full of bravado, and hungry for meaning. His world revolves around beers with his mate Jean‑Yves, evening rides with his little sister Claire, and the impending question of what comes next. Totone and Jean‑Yves drink, smoke, bicker, and laugh, and in their friendships, you see echoes of teenage summers all over the world.

The countryside setting gives these rites of passage a kind of intimacy to the testing of boundaries, outgrowing innocence, and feeling loss for the first time.

Coming to Australian cinemas 24/07/2025 and New Zealand 02/10/2025

Won Cannes Film Festival 2024 prestigious Youth Prize in the Un Certain Regard category and was nominated for a Camera D’Or

Went on the win Best Female Revelation and Best First Film at the César Awards 2025.

Directed by: Louise Courvoisier

Produced by: Muriel Meynard

Written by: Louise Courvoisier & Théo Abadie

Cinematography: Elio Balézeaux

Editor: Sarah Grosset

Starring Clément Faveau, Maïwène Barthèlemy, Luna Garret, Mathis Bernard, Dimitry Baudry

There is a single moment in the film that feels like everything shifts. Totone helps his father, Jacques (a quiet man hardened by years of hard labour), out of an embarrassing predicament, but with devastating consequences. In a heartbeat moment, the tone shifts to heartbreak. Childhood takes a blow it won’t recover from.

Claire, Totone’s younger sister, emerges as the film’s emotional linchpin. Luna Garret gives a performance both poised and penetrating: a child torn between dependence and resilience, grief and hope. One scene of exquisite simplicity has Totone crouch beside her in the hallway, helping her into socks before school. That tender moment with the almost imperceptible nervous smile on Totone’s face is exquisite and a testament to the combined skills of the crew- the director, the cinematographer, the editors, the actors.

Louise Courvoisier directs with a quiet promise: to show without telling, and to feel without preaching. She prefers small moments over sweeping gestures. She doesn’t lean on a score to manipulate your feelings; instead, the ambient world—squeak of tractor, rush of wind, hum of countryside—fills the spaces between dialogue. In every scene, she gives her actors room to breathe. A slight glance, an uneasy pause, the subtle droop of a shoulder—these micro-expressions speak volumes. Whether coping with grief or simply waiting for dinner, the characters are luminous in their unguarded states.

Parallel to Totone’s grief journey is a subtler, symbolic struggle: to remake his father’s signature cheese. He wrestles with milk and rennet, struggling with consistency, temperature, faith. It’s a ritual of inheritance, a half-conscious bid to preserve memory. A handful of early failures—the curd too cosy, the whey too watery—give way to a breakthrough. That quiet moment when he tastes the first batch, presses the wheel, holds it in his hands—simple triumph becomes transcendence. You feel the pride, the sorrow, the hum of hope.

The supporting performances of Mathis Bernard’s Jean‑Yves grounds Totone’s erratic energy. He’s the friend who stays when everyone leaves, whose presence is felt by all of us as we watch and reflect who was always there for us as teenagers. Maïwène Barthelemy, as Marie‑Lise, radiates earthy calm. Her scenes with Totone suggest a fragile, unspoken comfort. The performances feels like nothing is rehearsed or polished. It’s a sign of both natural directorial style and brave casting. These are young actors carrying a film on tiny shoulders, and they deliver.

Although set in rural France—the kind of place made for postcards—Holy Cow resists kitsch. Courvoisier uses nostalgia as a lens and you feel light filtering through tractor windows, taste the heat in the broad midday sun and sense the weight of tradition tied up in hay barns and wooden presses.

Sarah Grosset’s editing is unflashy but precise. Transitions between past and present (a childhood fishing trip, a father’s review of a finished cheese, the present guilt-wracked Totone) are handled with clarity. There’s no confusion, only continuity. The choreographed soundscape is likewise thoughtful. Louder moments—the soirée, the wreck—crash against silences and wind-whispers. Nothing feels pasted on. It’s all part of the fabric. What makes Holy Cow resonate is in its depiction of how life is ordinary; grief can be beautiful. Childhood is brutal sometimes; adulthood never comes unscarred. Those universal truths come through in the movie as fresh, personal, tactile. Teenagers everywhere find in Totone their reckless hope. Children everywhere understand Claire’s silent bravery. Families everywhere see their own tragedies and triumphs in the shifting frames.

Holy Cow is a rare debut that trusts audiences to feel, not just consume. Louise Courvoisier’s film is a slow hymn to love, loss, and the milky membranes of memory. It’s about life’s simplest actions: helping a parent, riding a scooter, making cheese—which, under grief’s glare, become acts of care and defiance. The performances—especially by Clément Faveau and Luna Garret—anchor the film’s lyrical drift. The visuals and sound invite immersion; the story invites empathy. It’s 92 minutes of living cinema: unhurried, unembellished, unforgettable.