The Persian Film Festival – founded by Palangi in 2011- is a celebration of identity, memory, and bold creative resistance. But before he was curating daring new voices, Amin was always telling stories of his own.

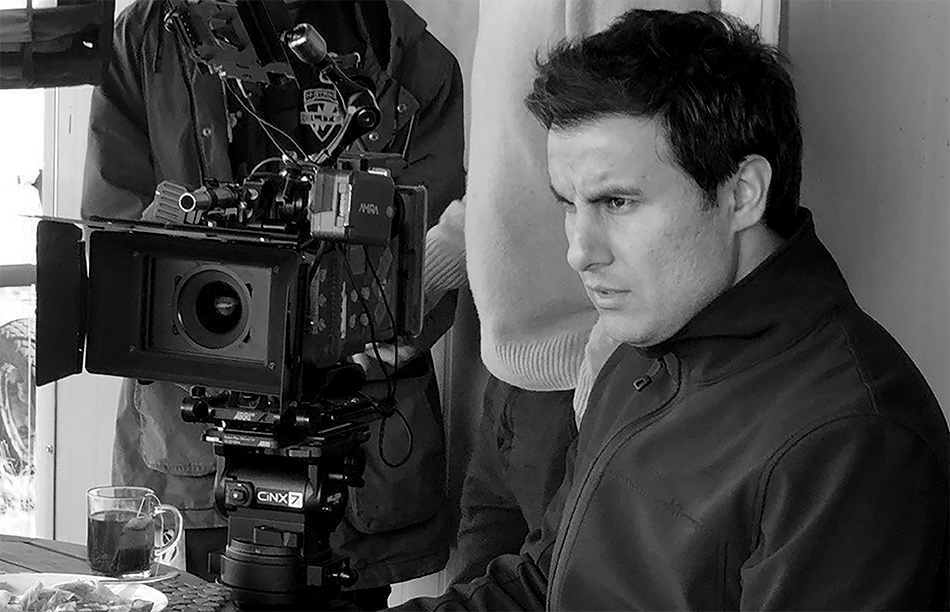

His award-winning debut documentary Love Marriage in Kabul won the Audience Award at the Sydney Film Festival (SFF) 2014, and Best Direction from the Australian Directors Guild, as well as introduced him to international audiences, being broadcast in over 26 countries. His most recent feature Tennessine premiered at the SFF 2023, received an ADG nomination, and was released in cinemas in April 2024. It will premiere on SBS on May 1. He’s also in development on a new feature, Common Ground, with acclaimed producer Yves Spence.

With artist parents who run a gallery in Surry Hills in Sydney, and a childhood steeped in visual storytelling, Amin’s creative lens has always been one of layered observation – human, metaphorical, and deeply diasporic.

You founded the Persian Film Festival. Has the vision evolved over the years?

Amin Palangi: This is our 11th edition. We started in 2011, though we did skip a couple of years during COVID. From the beginning, the festival has been about offering a platform for independent voices — and now, more than ever, those voices are daring. I have watched over 70 features and 300 short films this year. The migration patterns, the cultural shifts — they’re all reflected in the stories.

So what’s the heartbeat of this year’s program?

Daring. That’s the word. I borrowed it from the filmmakers. These stories are courageous — especially those from within Iran. I don’t work with state-funded films, not because I discriminate, but because the narratives often lean toward propaganda. I prefer a “tasting plate” of cinema — stories with depth, ambiguity, contradiction. Films that reflect life. Even if a film supports the current regime but tells a real human story, I’ll program it. But I’ve also become more open in my resistance — and more careful. Because many filmmakers inside Iran face real consequences for sharing their work with us.

We previewed Googoosh – Made of Fire— and it floored us.

It’s powerful, even for Iranians. Everyone knows her but many don’t know the full arc of her personal history. The film does an extraordinary job of threading her life through Iran’s political upheavals. It’s layered, poetic, and deeply necessary. That one was an essential inclusion for me.

Do you feel Persian cinema has changed in Australia over the years?Definitely. I approach this work emotionally — as someone who migrated here as a teenager, whose parents are artists, and as someone who straddles multiple cultures. I want future generations of Iranians in Australia to see themselves reflected in something more nuanced than just headlines. I’ve lived here since I was 17, I studied here, I work here — Sydney is home. That in-between space, that sense of cultural duality, really defines the festival’s perspective.

What core themes have emerged this year?

Courage is a big one. Iranian filmmakers, like those in Palestine or other suppressed nations, face immense personal risks. Every story is a kind of defiance. But it’s not all political — we also have deeply human stories. Cause of Death: Unknown, for instance, is about a group of strangers in a van, one of whom dies suddenly. There’s money involved, secrets. It’s a human thriller — quiet, profound, deeply Iranian, but also universally resonant. That’s smart-house cinema.

And the short films?

I love our short film session. Short filmmakers don’t need the same institutional support or approval, so the stories are often raw, fresh, and deeply personal. There’s gender parity, too — we’ve made sure to spotlight female filmmakers. The themes are wide-ranging: love, memory, desire, fear. And joy. There’s joy too.

How do you navigate censorship — especially knowing some works are controversial?

I avoid films that are overtly pro- or anti-anything. Good storytelling invites reflection, not instruction. That said, I’ve become more direct in my programming. I used to be more cautious for fear of getting filmmakers in trouble. Now, many of them are already openly resisting. I’m just the vessel for the voices. I present their work to the world.

Do you have another favourite film festival?

Sydney Film Festival is my Christmas. I take 10 days off every year just to immerse myself. I used to be a projectionist there when we screened 35mm at the State Theatre. I was a student at AFTRS in 2006 and 2007 — it feels like family.

We have a lot of young readers — how did you find your way into the industry?

I always loved art. But it was a writing teacher, Billy Marshall Stoneking, who truly shaped me. His four-day storytelling workshop in Melbourne blew me away. He encouraged me to study screenwriting at AFTRS. That led to directing. Australia is a place where, if you want something and you work at it, you can make it happen. That’s not the case everywhere. Now I make films, teach, and run the festival — and I’ve come to see that all of it is connected. Each role is a way of voicing something — from the perspective of a professional migrant and a cultural bridge. That’s who I am. That’s what I do.

The 11th Persian Film Festival will be held from 24th of April to 11th of May 2025. The program will include an official competition in feature, and short film categories where the Festival Jury will present the Golden Gazelle Award to the best film in each section. The festival will open in Sydney and will tour to Melbourne (1-4 May) and Armidale (9-11 May).