Corals may look like colorful rocks or take root like plants, but they are made up of thousands of tiny animals called polyps. When the environmental conditions and moon cycle are just right, they release egg and sperm bundles into the ocean for fertilization. This natural event, called broadcast spawning, can coincide with the similar activities of many other marine creatures, such as sea cucumbers, who also use the lunar cycle as their cue. This forms an awe-inspiring “mating ballet” when the reef comes alive.

The timing is precise, as each coral species may spawn within a 10- to 30-minute window on potentially only one night of a year. They also have amazing sensory abilities to help move to where they want to settle.

Malé-born biologist and coral tank technician Coco explains why research into corals is so critical: “While 99 percent of the Maldives is under the water, little is known about coral spawning. We’ve been monitoring coral spawning since March 2019 as part of a project started by our coral mama Philippa Roe, trying to find a pattern. Coral eggs and sperm are vulnerable to climate change, which is why we’re investigating species diversity and reef replenishment.”

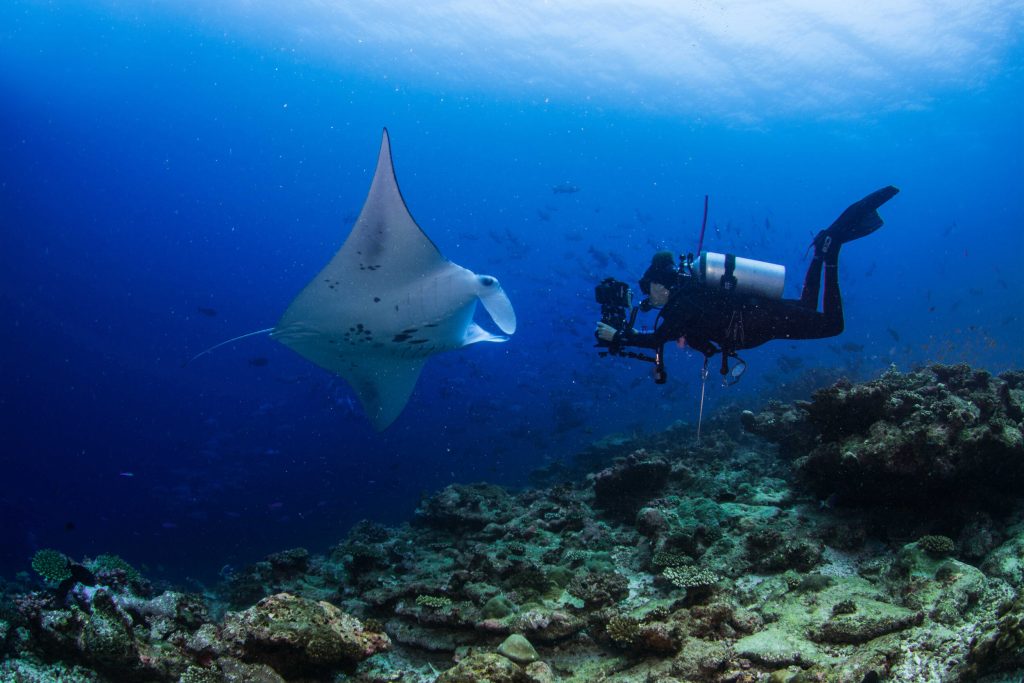

The Maldives is home to the world’s seventh-largest coral reef system and the fifth most biodiverse. The health of its reefs is vital for tourism, fisheries, and the physical resilience of the atolls themselves. One of the biggest successes to date has been the protection of critical habitats on Laamu Atoll as nationally designated Marine Protected Areas and the whole atoll as a Mission Blue Hope Spot.

The results of the research will contribute towards a better understanding of coral reefs, feeding into more effective marine conservation and protection in the Maldives.

“In the oceans, during coral spawning, there is a high probability that the coral larvae will not survive,” says Coco, “Other marine animals snack on these floating coral babies. Even when they do attach, the ocean conditions may be too challenging. Boulder corals are easy to damage but slow to grow, at less than 1 centimeter per year, but these give our atolls their strength.”

The marine biology team based at Six Senses Laamu started in 2011 with just one full-time marine biologist employed by the resort. As the size and goals of the team grew, the resort sought to bring together the greatest minds in marine conservation to find innovative solutions to Laamu’s most pressing issues.

Several years after opening, the team has grown to over ten specialists, consisting of resort marine biologists, sustainability experts and community outreach specialists, as well as those hosted from three partner NGOs: The Manta Trust, Blue Marine Foundation and The Olive Ridley Project. With such a large resource of experts, research expanded to cover a multitude of topics. In July 2018, as the need to unite these efforts under one banner grew, the Maldives Underwater Initiative was formed.

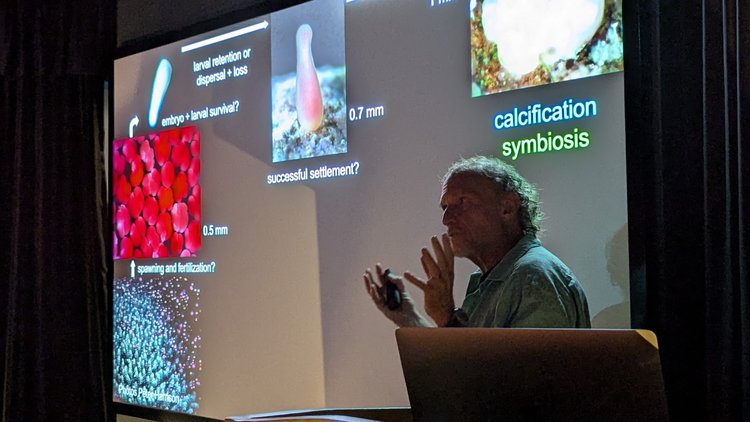

The MUI team has successfully nurtured thousands of tiny “recruits” (larvae that have settled on travertine tiles), which they keep for at least two years in dedicated tanks provided by the Coral Spawning Lab UK. From the first trial in March, conducted in collaboration with Prof. Peter Harrison, which led to 262 babies, a spawning in November led to 1,200 successful recruits, and another spawning in late November led to up to 800 recruits on a single tile! Coco is still counting these.

Conservationist Steve Backshall and Bristol University Professor Steve Simpson are other key experts who advise the team throughout the year.

Coco’s tank conditions are optimal, resulting in strong and healthy corals, which are an orange-brown colour due to zooxanthellae, or photosynthetic cells, which live in the tissues. In addition to providing corals with essential nutrients, zooxanthellae are partly responsible for all the unique and beautiful colours.

“When corals become physically stressed, the polyps expel their zooxanthellae,” Coco says. “They turn white, which is why we describe it as ‘coral bleaching’. If the polyps go for too long without zooxanthellae, they can die. Coral reefs have experienced severe, widespread coral bleaching both in 1998 and 2016. When bleaching happens, it affects the ecosystem itself. The fish decline, and the sharks don’t come up to the reefs. We have seen a big connection.”

Alongside coral fragmentation and replanting onto frames, coral spawning is a more natural way to research how to restore reefs in the Laamu Atoll and the Maldives in general. “Spawning increases the genetic diversity because we’re collecting the bundles of eggs and sperm, which means that some of those corals are more likely to be resilient to challenges. Because of this, they have a higher chance of surviving bleaching in the future because they have a higher diversity. We’re also testing stress levels. We might be sending a coral colony into space!” said Coco.

Along with the Manta Trust and the Olive Ridley Project, Six Senses also partner with Blue Marine Foundation and Maldives Resilient Reefs. Afaaz is based at Six Senses Laamu as the Resort Research and Fisheries Officer, joining Coco in his passion for the reefs and ocean around us. Afaaz comes from a fishing family, but having noticed changes in fishing patterns and troubled by the lack of fisheries research, he embarked on a career in marine science, starting with an internship with Maldives Underwater Initiative.

His efforts centre around protecting grouper populations and research on grouper spawning. He is also working to support our sustainable resort reef fishing program, Laamaseelu Masveriyaa, which means “exemplary fishers” in Dhivehi.

“This is our code of conduct. It ensures the entire process from reef fishing to catch volumes and purchasing is sustainable. We also work with the government to promote a better documented and more sustainable fishing industry in the Maldives by protecting threatened species or species for export that are below their size limits,” Afaaz explains. “Some fish mature very late, so we have to protect them until they reproduce.”

“In return, we work to protect our local fishers’ livelihoods. I come from Gaafu Dhaalu Atoll in the Maldives, so I feel a great responsibility, and I hope the Laamaseelu Masveriyaa program will eventually become a nationwide model.”

After all, people don’t live in the ocean, but we all depend on the ocean to live.