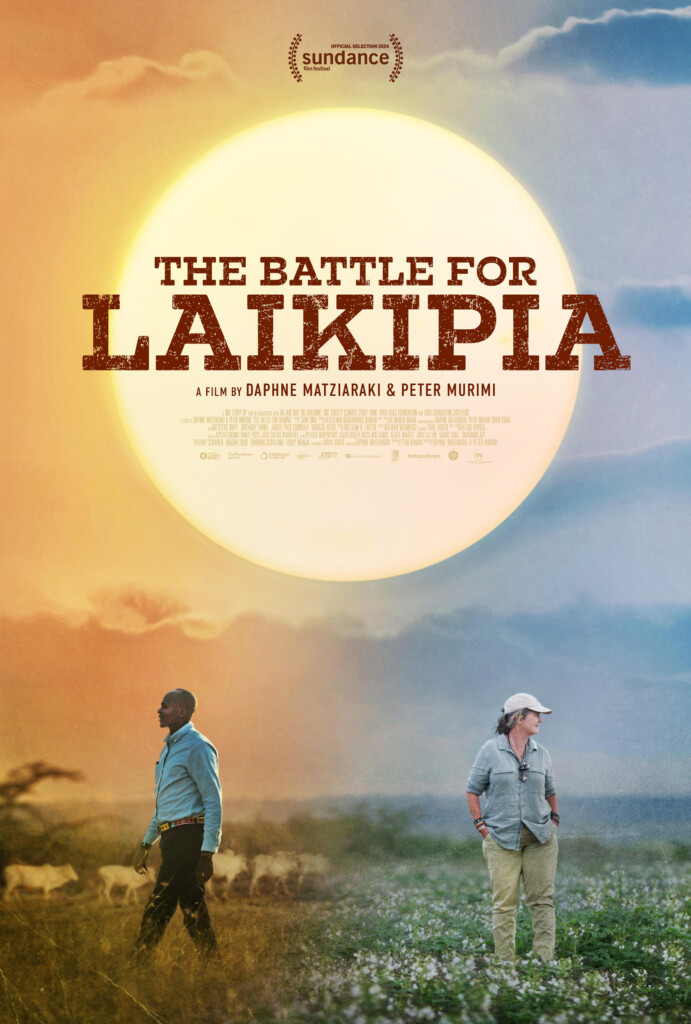

This is a film about resources, restitution and retribution. It’s set in the glorious high plains of the Laikipia region of Kenya, a wildlife conservation haven with a problem: the rains have stopped.

The Battle of Laikipia was filmed over a 6 year period that started with a drought, and during which time, like a lot of places in the world, every year was worse than the last. We watch community tensions that have simmered for years brought to boiling point, as the fight for grazing land amps up and an election looms. The pastoral communities, who have lived off the land for centuries, need grass to feed the cattle on which their livelihoods depend. It’s in short supply. The film follows Simeon of the Samburu people, his family, and his tribe, as they try and navigate the new realities. The white ranchers, mostly descendants of British colonial transplants from the early 1900’s, will go to extreme lengths including guns, fences, and a lot of driving around in jeeps, to police the boundaries of their enormous estates. As the land dries up, they’re no longer willing to share. As Maria, the matriarch of one such rancher family who’s attempting to hold their ground says in the film, “It’s like a little bubbling volcano.”

Both sides feel deeply connected to the country and the land, and the filmmakers hold back, giving everyone a chance to speak, and the audience the space to make up their own minds. The Samburu people have a rich culture that is centred around the cattle; they drink its milk, eat it’s meat, gift it, mark the chapters of their lives by it, are buried in it’s skin. When an enormous number of cattle are lost, it’s a poignant cross- generational kind of loss. from which you sense a family might not recover. The white ranchers are also entrenched, both emotionally and financially. The difference is in the ranchers connections to power, highlighted as we see their meetings discussing the fate of the pastoralists, and their calls to family in the U.K. You imagine if things really did hit the wall, one side would have somewhere else to go.

Follows Simeon, a member of the Samburu people, the tribe that has grazed the land for centuries, and Maria, the matriarch of a white family 4 generations deep into land ownership in Laikipia.

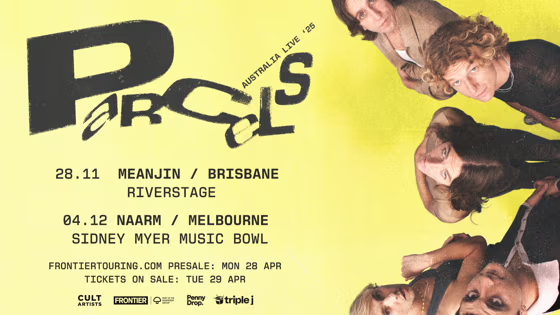

Premiered at 2024 Sundance Film Festival where it won Producers Award for Nonfiction. Has been a hit at FIFDH Geneva, CPH:DOX, Seattle International Film Festival, Sheffield International Documentary Festival, Sydney Film Festival, HotDOCS Canadian International Documentary Festival winning the Land|Sky|Sea Award, Torino CinemAmbiente winning Best International Feature Film, and Guadalajara International Film Festival where it won Best SocioEnvironmental Cinema Film, and next stop is the Galway Film Fleadh Festival for it’s Irish premiere and then the Durban International Film Festival. MetFilm Sales has international rights.

Co-Directed by Daphne Matziaraki, who previously directed Academy Award-nominated short 4.1 Miles, and Peter Murimi. Both directors are also cinematographers for the documentary along with Maya Craig. Matziaraki and Craig co- produced with Toni Kamau of We are not the machine. Executive producers are Roger Ross Williams and Geoff Martz of One Story Up. Edited by Sam Soko. Original score by William Ryan Fritch. Our in-depth interview with Daphne Matziaraki can be found here.

Co-Director Daphne Matziaraki worked in Kenya 20 years ago for the United Nations and was powerfully compelled to tell the story of the region which, as she told Irresistible, she sees, “as a microcosm of the community and climate issues that the majority of people will face, one way or another.” Our in-depth interview with Daphne Matziaraki can be found here.

Peter Murimi is an award-winning Kenyan documentary director. He previously direceted I Am Samuel in 2020 and in 2004 he won the CNN Africa Journalist of the Year Award. As he told Irresistible, “This is a story about marginalised people who live on the fringes and who are not always taken seriously. Colonialism, displacement, inequality, climate change and the power plays around all these things are all there in the film.”

We see all of this and more. Violence follows on, as always, from desperation. It’s a powerful message that will come up time and time again in communities like Laikipia, and every other town and neighbourhood where the pressure-cooker issues of a changing climate, resource allocation, power and ownership will become not just political, but a dance to the death of survival.