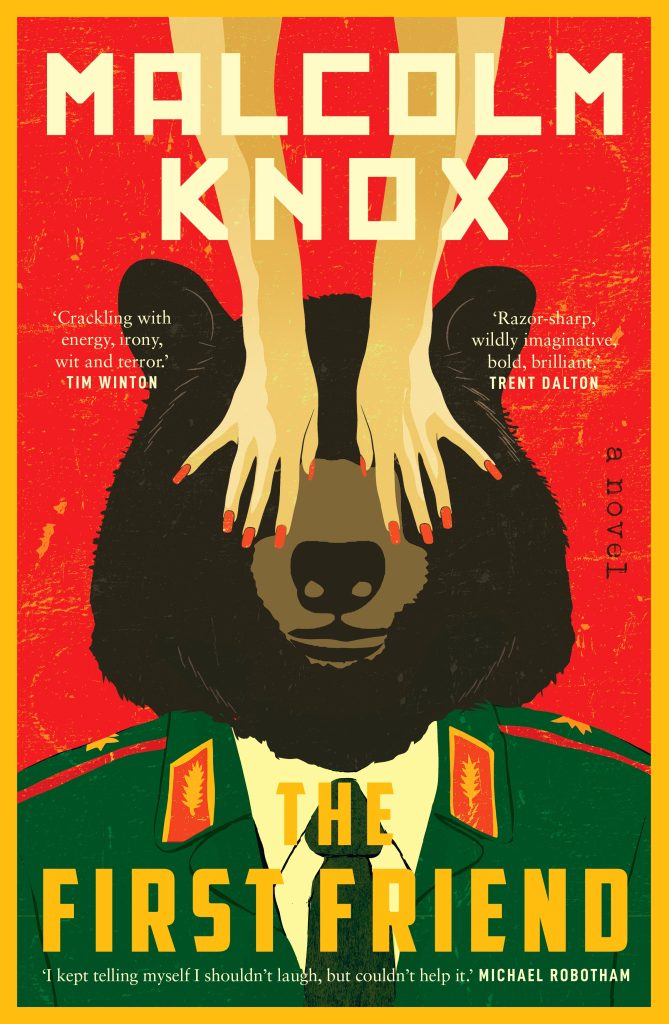

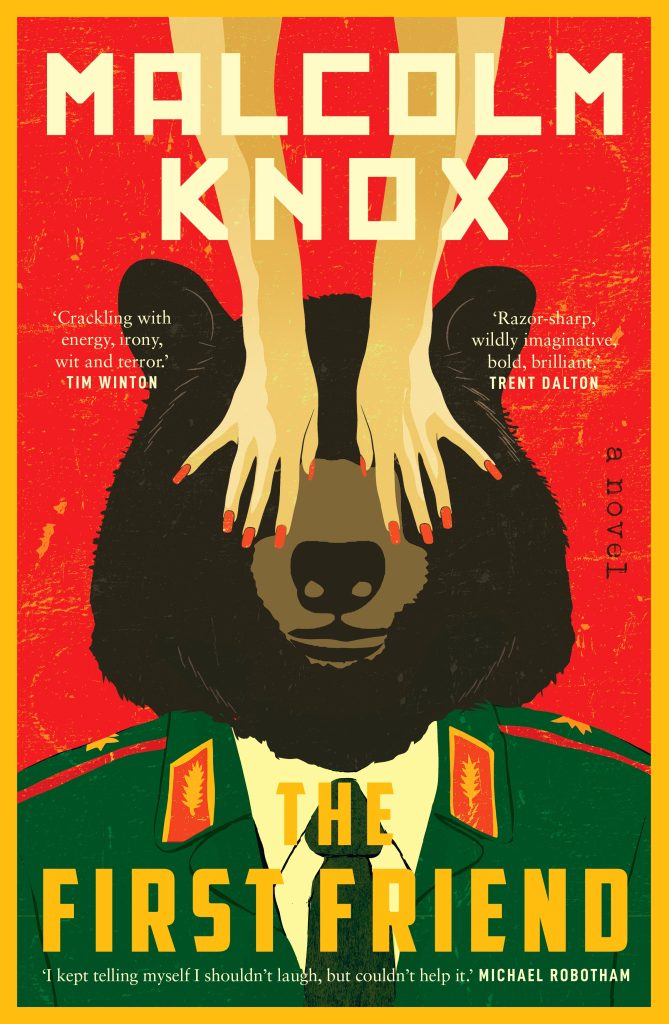

The First Friend is set in Stalin’s 1938 Soviet Union, and is a black comedy, a thriller, a survivor’s tale, and a close up examination of a monster and a monstrous society. Longlisted for the 2025 Walter Scott Prize for Historical Fiction, the fusion of history and fiction has Lavrentiy Beria, the real leader of the Georgian republic, prepare a Black Sea resort for a visit from Josef Stalin.

As in all of Knox’s work, the relationships are the thing. Beria has a best friend- come- dogsbody- come- driver Vasil Murtov, who is married to Babilina. The couple have to speak in code and the family need to survive the increasingly unpredictable Beria.

It’s a tense reflection on Putin’s Russia, Trump’s America, Xi’s China and Murdoch’s planet Earth, on truth and power and propaganda.

Since 1994 Malcolm has written for the Sydney Morning Herald and has won three Walkley Awards and a Human Rights Award. His novels include Summerland; A Private Man, winner of the Ned Kelly Award; Jamaica, which won the Colin Roderick Award and was shortlisted in the 2008 Prime Minister’s Literary Awards; The Life; The Wonder Lover; and Bluebird. His many non-fiction titles include Boom: The Underground History of Australia; From Gold Rush to GFC, which won the 2013 Ashurst Business Literature Prize; and Bradman’s War, shortlisted in the 2013 Prime Minister’s Literary Awards.

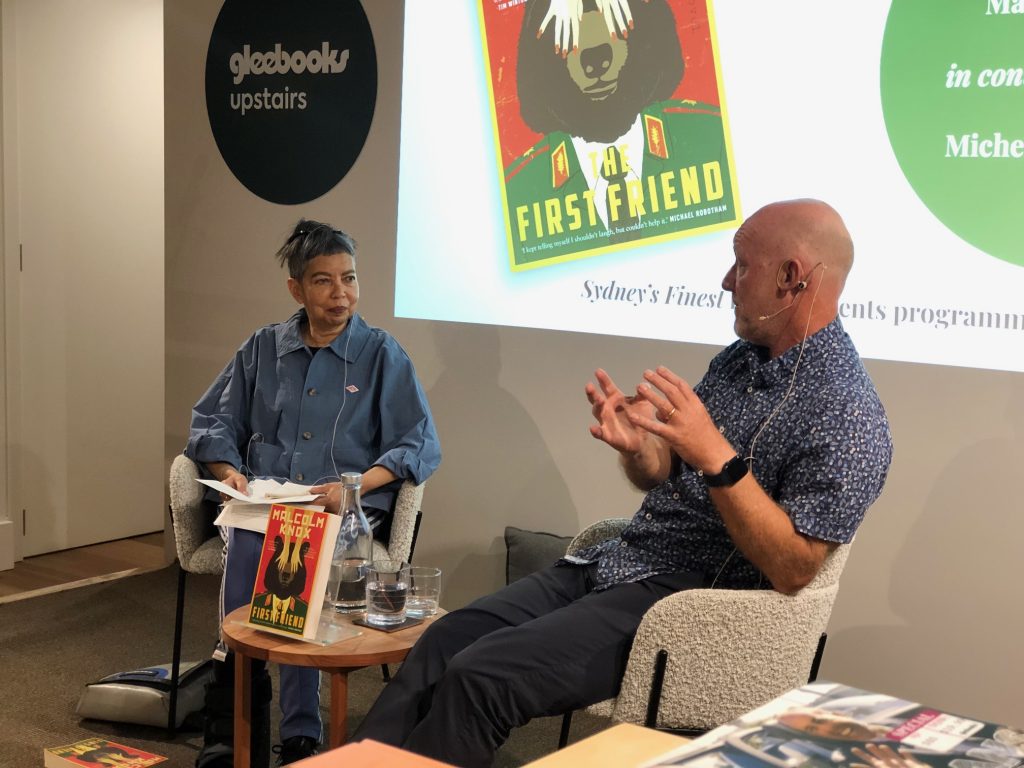

It was only a matter of time before he sat down with Irresistible, and so we chewed the fat to find out what’s dragging him away from the beach and into one of the darkest times of the last century.

Congratulations on The First Friend. You’ve said before that the pandemic gave the project a bit of a jump start. What happened?

I’d covered the Tokyo Olympics and I had to do two weeks of hotel quarantine at the Marriott down near Circular Quay in Sydney. It’s a lot of time to have on your own, and I needed to distract myself. I didn’t want to fritter my time away, or just sit there, so I dived in pretty obsessively. I was in a little box, and the windows didn’t open. I didn’t see a single person and the food was left outside the door, so it really filled my head entirely for the whole time. I had thought about the story before, but I established that first real rush.

Did it all come out quite fast then?

I’m a real momentum writer and I write very quickly in the first draft. It’s nothing like the final draft, but it’s a sort of a beta version. The central characters really came together during that time, and I felt the compulsion to make the principal relationships between Beria, Murtov and Babilina coherent. I didn’t focus too much on Georgia and the geographical details in those early drafts.

A lot of your work has been firmly rooted in Australia. Where did the impulse come from to write about the Soviet Union?

I did go through a period of setting the book in a dystopian fantasy land where it’s not actually Russia, and the Beria character was not actually called Beria. But I was always relating everything back to Soviet Georgia, and so it seemed like I was adding a layer of interference between the reader and the story that didn’t need to be there. Soviet Georgia is certainly off the beaten track for an Australian writer, but it felt very instinctive, and the natural place to set a book about a world where everything is made up, where everything is fictionalised for the purpose of putting people off balance.

Were world politics and Covid-19 feeding into that paradigm?

I was certainly thinking about the book when Trump was in power for the first time. But it wasn’t just Trump. There was this sort of stacking effect made by all the people who were using the same technique; flooding people’s minds with an excess of stuff that looks like information. I was trying to find a lens through which to look at this and to make sense of the world we were living in. It feels even more needed now, but it was very much the case in 2020 and 2021 when I was first conceiving of the idea. We’re not in a world where we are deprived of information and we’re sitting around wondering what’s happening. The economy of information is the opposite. We’re given an excess of information and kept off- balance. We don’t know what to believe. That was how the Soviets operated.

Is that what you found when you researched the Soviet era?

It’s often assumed that in that world everybody was walking around in the dark deprived of information. But if you look at the newspapers from that time, they’re just bursting with facts about production or international affairs or the doings of the leaders. There’s no trivia in Pravda. Now, those facts were completely invented, but that was the means of control; to overwhelm people. I feel like that a lot of the time; I’m just overwhelmed with stuff that looks like the truth.

How do you compare that period with the times we are living through now?

There’s nowhere in the world right now that is deploying anywhere near that degree of violence against its own population, and I don’t think we’re heading towards a period of that level of cruelty and barbarity. The metaphor for me rings true in the cult of personality, and the comfort that a great portion of the world’s population feels in the strong man authoritarian leader. We see that all around the world now, not just in the USA. And I think we’re seeing it at a local level too, in clubs and businesses, and small town politics. To a degree the Australian election we just had was a rejection of that idea, but people gravitate towards these kinds of politics and leaders at times of uncertainty.

The book explores the 20th Century Russian version of that idea- Stalin.

Stalin was a cult of personality in the Soviet Union. He himself is not a large part of the book, but there’s a sense of the replication of little Stalins, like Beria in Georgia. He had posters of his face all over Georgia when he was Governor of that country. There were towns and street and squares named after him. We call it branding now, but it was invented as a mechanism of maintaining power a long time ago. The people in Georgia believed Beria was a man with a kind of mystical power to save them.

Central to the book, and to much of your work, is the dynamics of a friendship, in this book its between Murtov and Beria.

I would say in all of my novels the central relationships have been friendships, and ones that have been affected by power flips or imbalances. Throughout my own life, friendships have always been affected by those changes, and it’s a reality that people’s lives go in different directions. My question is always, how do friendships, and other intimate relationships like marriages, survive? In my previous work, what has been at stake has been relatively small scale, like the friendship itself. I was restless to explore the same dynamics where the stakes are a lot higher, like life and death.

A lot of people have felt their friendships being tested by politics and world events recently. Has that been easier for you to navigate as you have written about those tensions so much?

I did have friendships tested in my earlier years. Things that I’ve put in my novels have definitely placed a strain on my relationships. I don’t know if I’m weak or diplomatic or emollient, but I always try and get on well with everybody, although being a compromiser can lead one into compromising situations! I do know people who admire Trump and strongman politics, and really belong to that cult of bossism- where a person who’s made a lot of money, like Elon Musk, is somebody who deserves to be almost worshipped because of what they’ve done in business. I don’t necessarily like it, but I’ll always put a friendship first, and try to steer clear of direct confrontation.

As male friendships are such a theme in your work, who are your best friends?

My close circle of friends has been the same people since I was between 9 and 18 years old. Most of them are school friends, and a couple from university. I do have close friends that I’ve made as an adult, but they’re different kinds of friendships. They’re often ones where you can talk really, really frankly in a way that sometimes you can’t with your oldest friends. With those really old friends, I find we don’t often talk about the big stuff, we’re always straight back to childhood.

The other big tension in the book is around the mood swings of these mini-dictators and how dangerous they can be. There is some universality in those kinds of dynamics that everyone can relate to. Did you draw on your own experiences of power structures?

I think in families, children can often have to walk on eggshells around their parents moods, so I think a lot of people can relate to that.

Certainly I’ve been in workplaces where the laughter in the meeting room is nervous. The laughter of people who are observing some kind of tirade, and who are not in the crosshairs at that moment, but know it could be them next. Bosses I’ve had have been manipulative, and their unpredictability was something intentional and crafted to exercise power over people. I have absolutely been afraid in those kinds of situations, and seeing the reflected fear in others was something I drew on for the book. Seeing adults shaking and crying at work had a big effect on me, and watching those kinds of predators pick off the weakest in a group was striking.

There’s definitely a similarity in the historical research I did into people like Stalin and Beria who were also intentionally unpredictable. I suppose I’ve long been fascinated by the effect of these kinds of characters on those around them; the fear they create. I was definitely focussed on that when I was writing – on people who are sadistic and cruel.

In the book, how afraid is Murtov of Beria do you think?

Murtov is a bit of a mystery to the reader. We don’t know how scared he is because he’s working hard to conceal any of those feelings from both Beria and his wife Babilina. We have to work it out more from how scared other people are. Beria values the friendship more highly than Murtov. Beria doesn’t have anyone or anything else in his life as he’s a genuinely psychopathic individual. I really enjoyed teasing apart the threads and complications of that relationship and I found a lot of the humour was in the mystery around Murtov. Is he just trying to survive, does he have a plan, or is he completely passive?

That other big relationship in the book is the marriage, and what happens inside marriages is another theme in your work. How did you make the relationship between Murtov and Babilina fit into the context of the story?

The marriage and the threat to it because of this very dominant friendship between Beria and Murtov was always a cornerstone of the book. I knew that the husband and wife had to communicate in a secret code because of these outside threats. The primary question was how can love survive in a world dominated by fear, where the two lovers can’t trust each other to talk candidly, even at home. I raised the stakes higher than I have in previous work by making it not just about the survival of a marriage, but by making the children and their survival key.

Beria is a real historical figure. How much of the story in The First Friend comes from the historical record.

Murtov is a completely fictitious character, but in real life there was a family who adopted Beria when he was a child, but that family were all killed.

Beria is a real man of mystery, because all of his records and documents were thoroughly destroyed, and his name was erased from any other records, even the encyclopaedia. After his death, thousands and thousands of people in the Soviet Union were sent a little bit of paper about the Bering Sea, between Russia’s far east and Alaska, and they were instructed to cut out the entry on Beria and paste in this entry on the Bering Sea in its place. That was the extent to which the powers wanted him gone. The whole thing is about disinformation and lies and propaganda.

There are lots of writings about Beria, but all the information is gleaned from writings about Stalin or other important figures at the time. At the end of the book we see Beria promoted and demoted at the same time, and that did happen. He gets to Moscow and is brought into the inner circle. But he’s brought in as a thug and kept in the shadows. Within his first year in Moscow he had succeeded Nikolai Yezhov, the head of the secret police, who was killed on Stalin’s orders.

What happened to the real Beria afterwards?

In the war, Beria went on to become the chief of everything. Whenever Stalin had a problem, he made Beria the minister of that thing. So he was head of the Gulag, logistics and transportation, religion, and ideology. At the end of the war, Stalin made him head of the atomic bomb program, and he was an incredibly effective executive. He developed the atomic bomb and then the hydrogen bomb for Russia within four years. At the end of Stalin’s life, he turned on Beria. Then Stalin died. There were rumours that Beria even killed him, none of them substantiated. Beria effectively became the chief of the Soviet Union, he ran everything with a member of Stalin’s Politburo, Georgi Malenkov, as a figurehead.

And in 100 days, he was the most liberal reformer that the Soviet Union ever had. He freed a million people from the Gulag. He wanted to set free all of those Eastern European countries. He lowered prices, he began to demilitarise Russia. He was a great moderniser, and we’ll never know whether he was doing that because he was a genuine liberal, or because he was trying to distance himself from Stalin’s regime. The rest of the inner circle feared he was going to get rid of them all, so they staged a coup and executed him. That was in 1953 and he was 54.

Have you observed echoes of these times in modern day Russia?

In Russia, Putin has rehabilitated Stalin to some degree, not the ideology and not the mass murder, but the nationalism and the idea of the strongman. Beria will probably never be rehabilitated other than in some parts of Georgia where he is still known. I think about what happens in Russia now and see it fitting in with these old playbooks. Beria invented the air crash as a way of getting rid of enemies. He was doing it multiple times in the 1920s. People that got in the way of himself and Stalin would go down in unexplained aviation accidents.

One day we’ll know a lot more about what’s happening in Russia at the moment. We think of these as Cold War stories, but in a lot of parts of the world, these are the lives people are leading now. It’s still happening.

Did you do any research over in Georgia or Russia? Have you visited?

No, and that was intentional. Georgia was made by the Communist Party into a sort of a make- believe place. So, I didn’t want to turn the book into an of accurate rendition of Georgia because the whole point of it is that so much of the world has turned into something imaginary. Americans don’t know if Haitians are jumping into people’s backyards and eating their pets because their President has told them they do.

But now I’m really keen to go to Georgia. Its very, very interesting and has become a lot more safe for tourists. Everyone who goes raves about it. So, next year we have a tentative plan to go.

This is your seventh book. Are you already working on something else?

I’m actually working on a sequel to this book. It takes place immediately after the war and the key characters are Murtov’s daughter Melor, Stalin’s daughter Svetlana, and Beria’s son Sergo. It’s set seven years after the events of The First Friend, starting with VE Day and ending with VJ Day, and with these three characters there’s another triangle of relationships. Although two of the characters did exist, the situations I’m putting them in are invented, so it’s another hybrid of history and fiction.

You’re still very active in the Sydney Morning Herald. Do you split your week between journalism and fiction, or do you have breaks from one to do the other?

I write one to two articles per week for SMH. I’ve done it for so long I like to think I can carve my brain into two halves, and think as a journalist when I’m doing that work and think as a novelist when I’m doing that work. I’ve always carried on. As I get older, I think I’m becoming a little bit less skilled at doing that, my brain is becoming more porous and the wall is less effective. I think I am going to take breaks in the way to write novels in the way that more sensible people do.

Sydney Writers’ Festival

19–27 May 2025.