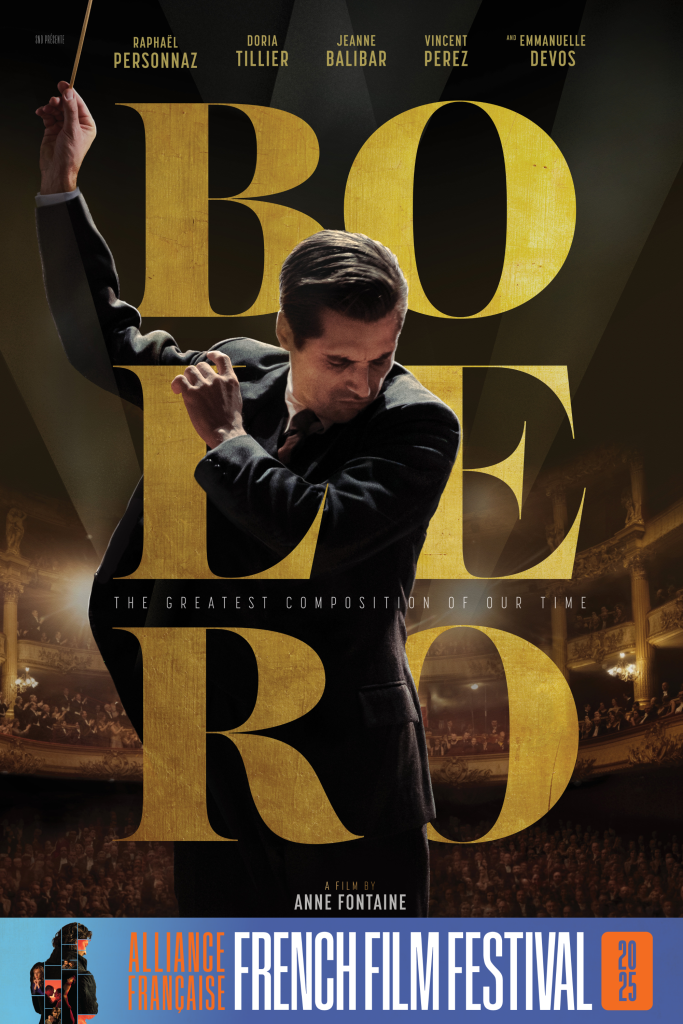

In writer-director Anne Fontaine’s latest triumph, Bolero, we’re invited to witness the haunting and hypnotic process behind one of the most enduring pieces of classical music ever composed. Set in the glittering yet gritty Paris of the 1920s, this sumptuous biographical drama delves into the life of Maurice Ravel, portrayed with disarming vulnerability by Raphaël Personnaz (The Princess of Montpensier, In the Courtyard). Though revered for his inventive orchestrations and refined style, Ravel finds himself paralysed by self-doubt and haunted by the suspicion that his greatest work may already lie in the past.

From the moment we first meet Ravel, he’s grappling with a commission that could redefine his career—or destroy it. Ida Rubinstein, the eccentric Russian dancer portrayed by Jeanne Balibar (César-winning star of Barbara), demands an erotic and sensual ballet score. Ravel’s once-flourishing creativity stalls, and the composer slips into an isolating spiral of uncertainty. As one character pointedly observes, “You live in the loftiness of art. An intangible world.” The film reveals how that intangible realm—where genius thrives—can also become a prison.

Paris in the Roaring Twenties is a heady mix of industrial modernity and avant-garde indulgence. Anne Fontaine and cinematographer Nicolas Chevreau capture this duality with painterly finesse: opulent salons stand in stark contrast to the smoky jazz clubs and steel factories humming on the city’s outskirts. It’s in this atmosphere that Ravel seeks fresh inspiration, but he struggles under the weight of his own insecurities.

Screening in the French Film Festival 2025

Directed by Anne Fontaine

Writing Credits Anne Fontaine, Claire Barré, Pierre Trividic, Jacques Fieschi, Frere Jean-Pierre Longeat

Produced by Philippe Carcassonne, Julien Deris, David Gauquié, Jean-Louis Livi, Philippe Logie and Patrick Quinet

Music by Bruno Coulais

Cinematography by Christophe Beaucarne

Editing by Thibaut Damade

Starring Raphaël Personnaz as Maurice Ravel, Doria Tillier as Misia, Jeanne Balibar as Ida Rubinstein and Emmanuelle Devos as Marguerite Long

The composer’s circle of confidants becomes both his lifeline and his downfall. Emmanuelle Devos (Mascarade, AF FFF23) plays the acclaimed pianist Marguerite Long, whose unwavering belief in Ravel’s brilliance offers him fleeting solace. Vincent Perez (Cyrano de Bergerac, Queen Margot) embodies Cipa, a loyal friend whose pragmatic calm contrasts sharply with Ravel’s turmoil. Adding further complexity is Doria Tillier (Mr & Mrs Adelman, La Belle Époque) as Misia, Cipa’s sister and the object of Ravel’s unspoken adoration. Each of these figures illuminates a different facet of the composer’s psyche—whether it’s devotion, frustration, or longing.

Like the iconic music that shares its name, Bolero unfolds in a gradual crescendo. Fontaine structures the film so that each sequence builds upon the tension of the last, mirroring the famous composition’s escalating repetition. Early scenes linger on Ravel’s writer’s block, his frustration evident in every encounter. As deadlines loom and social pressures mount, the tempo of the narrative quickens. Arguments flare, alliances strain, and the stakes feel increasingly dire. By the time the composer finally breaks through his creative barriers, the film has reached a feverish intensity—much like the thunderous final bars of “Bolero” itself.

This rising tension finds its most beguiling expression in a quiet but alluring moment in the film: Ravel asks a woman to put on a pair of red gloves, ever so slowly. The camera lingers on each subtle movement, turning an ordinary gesture into something both exquisite and excruciating. It’s a scene that encapsulates Ravel’s obsession with the sensual and the sublime—a fleeting metaphor for the slow, hypnotic build of his music, as well as the painful intimacy of his own unspoken desires.

Central to the drama is Ida Rubinstein, whose commanding presence both enthralls and unnerves Ravel. Balibar imbues Ida with a tantalising mix of confidence and mystery. She’s a woman who understands the power of spectacle—on stage, in high society, and even in her private dealings with the fragile composer. Their dynamic teeters on the edge of collaboration and confrontation, each pushing the other to extremes of creativity and self-discovery.

As Bolero reaches its own cinematic crescendo, Fontaine employs a daring shift in style to reflect Ravel’s unravelling mental state. The camera grows restless; images blur and cut abruptly, creating a sense of dislocation that mirrors the composer’s deteriorating health. Hallucinatory flashes of childhood memories, old love affairs, and half-finished scores swirl together, offering a window into the fracturing mind behind the masterpiece. This stylistic rupture is both exhilarating and heartbreaking. While the earlier acts showcase the glamour and vitality of 1920s Paris, the closing moments capture the toll that relentless artistic pursuit can take on a fragile psyche. Fontaine doesn’t shy away from the tragedy of a mind on the brink, even as she celebrates the genius that mind has given the world.