Denis Johnson’s novella from which the film is adapted was published in 2011, and shortlisted for the Pulitzer Prize in 2012, the year in which for the first time in 35 years no Pulitzer Prize for fiction was awarded as none of the entries could garner a majority. It’s a fitting echo of a story that is both massive and small, about everything and nothing, loud and quiet. The film adaptation is unlikely to stay similarly on the sidelines however, breathtaking in both its scale and nuance, and an extraordinarily sensitive, possibly career- defining, turn from Joel Egerton.

It was also one of the few big sales to come out of an otherwise slow market Sundance Film Festival, bought by Netflix for a very healthy sum, and so not only will it hit the small screen in due course, it could possibly also be a contender for best actor nominations next year.

The director Clint Bentley, along with his creative partner Greg Kwedar, has lovingly turned the original prose into a visual feast and a captivating examination of the lives of the people that laboured to build the dream of pioneer American expansionism.

The duo are having something of a moment, nominated for an Oscar for their adapted screenplay for Sing Sing, and still basking in the glow of their other recent collaboration Jockey.

The long arc of the story paints the whole life of Robert Grainier, poignantly showing the audience the significance of the smallest and biggest parts of a life. Some of the most powerful scenes are fleeting images or moments, presented almost as subliminal images, echoing the snapshots of memory. Adolpho Veloso’s camera work is both painterly and hyper-real, freewheeling and expertly structured. An original score by Bryce Dessner is suitably epic, grand and, when needed, still in its proportions.

Premiered at Sundance Film Festival 2025

Director Clint Bentley

Screenwriters Clint Bentley and Greg Kwedar

Producers Marissa McMahon, Teddy Schwarzman, Will Janowitz, Ashley Schlaifer, Michael Heimler

Casting Avy Kaufman

Composer Bryce Dessner

Costume Designer Malgosia Turzanska

Production Designer Alexandra Schaller

Director Of Photography Adolpho Veloso

Editor Parker Laramie

Vfx Supervisor Ilia Mokhtareizadeh

Starring Joel Edgerton, Felicity Jones, Kerry Condon, William H. Macy, Nathaniel Arcand

Robert Grainer has an unclear and lonely start in the early 1900s, orphaned from a young age, and not knowing what happened to his parents. In adulthood, he finds employment as a logger, heading out to work camps for months at a time, to build the railroads that the burgeoning USA is hungry for. He is isolated amongst these groups of men who barely know each other, until he meets Gladys, played brilliantly by Felicity Jones, and the two start a quietly massive love story that defines the rest of his life.

Will Patton, who has also recorded the voice for the audiobook of the novella, provides a rich and earthy narration that comes and goes, filling in some of Grainer’s introspective silences with phrases from the original work. It makes sure we are always rooted in the consciousness of the American West, and helps move the audience on from the heart- wrenching moments.

William H. Macy is scene- stealing in his portrayal of an explosives expert in the railroad camps, ruminating on the state of the nation and every man’s soul, and foreshadowing an uneasiness with the casual destruction of the natural world. Two other points of friendship seem to define Grainer’s life, that of a Native American storekeeper Ignatius Jack, played wonderfully by Nathaniel Arcand, and a forestry services worker Claire, played charmingly by Kerry Condon. As with the other figures in Grainer’s life, these friends depart from his world as easily as they arrive. The whole film leaves the audience with a series of indelible memories and images, and a story of a life that won’t be forgotten.

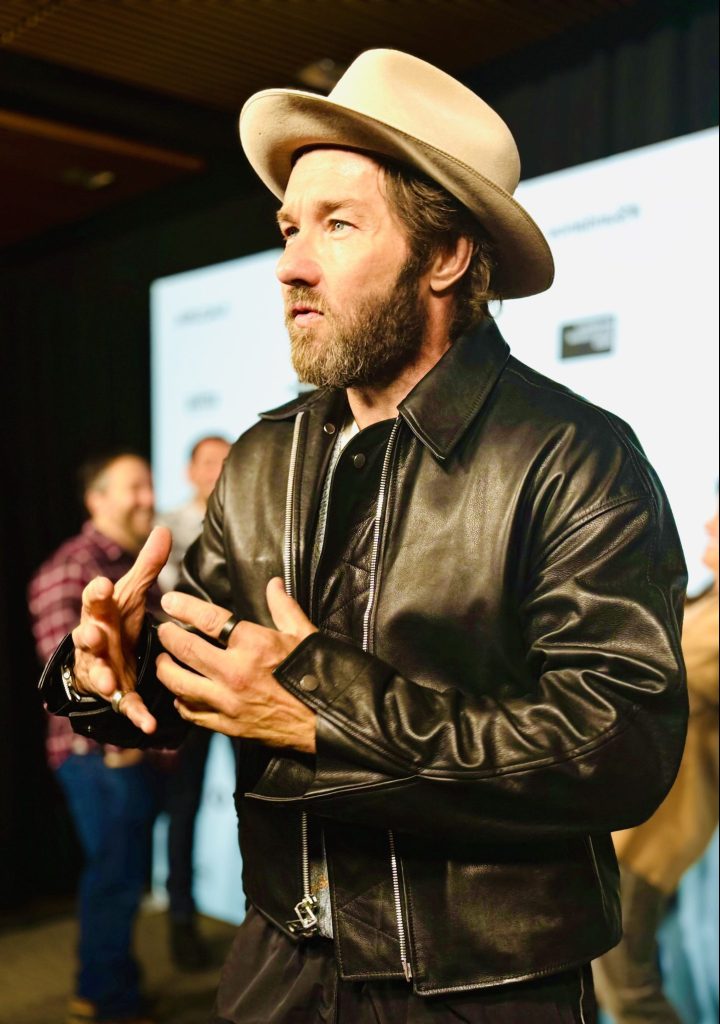

On the red carpet before the premiere at Sundance, Irresistible spoke to the director Clint Bentley, actor Joel Edgerton, director of photography Adolpho Veloso and production designer Alexandra Schaller.

The film is an adaptation from the novella. Did you think about adapting something first, or was it this particular story that led you down that path?

Clint Bentley: I always wanted to do an adaptation one day. I always felt very strongly that when a filmmaker does an adaptation they have to have a kind of kinship or spirit with the original writer in order to translate the work. I probably never would have had the courage to do this one, but some great producers had the rights to the book, and after they saw Jockey at Sundance they asked me to adapt it, and that’s what Greg and I did. It felt like a very good marriage.

Did you already feel that kinship with Denis Johnson?

CB: I had been a big fan of Denis Johnsons for a long time. He is one of my favourite authors ever. There are a lot of things in the book that I would never have been good enough or smart enough to write, but I love it.

This is a story about a period of American history and the changes witnessed in one man’s life. Is there a deeper resonance with the times we are living through now, particularly in the States?

CB: I think anytime you tell a story, if it feels timeless, it will always be relevant. Citizen Kane is as relevant now as it was when it came out. I think there are aspects of American expansion and American society that we don’t often see that I wanted to explore in this film, and that’s the people who are the hands and the feet that build our societies. The film is set in a certain time and is about a logger, but it could be set now about an Amazon worker, or in any part of the world. It has an evergreen quality.

We’re very close to the main character in the film. What did you take from being on that journey with him?

Joel Edgerton: Now that I’m a father of two young ones, I think the fear around losing family is definitely explored. My greatest preoccupations now are about my kids wellbeing. I read the novella years before I was involved in the project, but I was a dad by the time I was sent the script. That really worried me, I was a bit nervous about whether I should do the film or not. But that’s also a good reason to go to work, to face your fears, and I knew all of that was inside of me anyway.

There is great joy in the film as well. Was that easier to get into?

JE: I consider myself pretty easygoing in life, but I think the real challenge is that on screen some of the hard things can become too grim, so it’s about finding some moments of joy and lightness in the story, and finding the points of humour.

What were some of your favourite moments from the film?

JE: We have some beautiful moments that were unscripted, especially with the animals and the children. They are pure so what you get on screen is really pure and magic, so letting the camera keep rolling created some very special scenes.

Also I always feel good when I shoot a movie in open spaces. Where I grew up in the Inner West of Sydney was more rural than it is now, so it always feels good to get back to that environment.

What would you like people to take away from the film?

JE: I think that you can tell one person’s story, and the things that happen can speak to everybody. In this case, whether they’re people from a rural or blue collar background or not, it doesn’t matter. I think even if you live a corporate life, you can relate to the idea that life is short, and full of some really great things, and lots of hardships. Despite the terrible things that might happen, people are so resilient They keep moving. Time keeps turning. We absorb things. At the end of the day, even if awful things happen, life is worth living.

There was a lot of movement on your last project with the team in the film Jockey. Train Dreams is a lot more meditative. How do you manage such different imagescapes?

Adolpho Veloso: I feel like in the end, these two films are similar in that they tell the story of these two men to whom the audience gets very close to. Jockey wasn’t a period piece so we had a lot more freedom in movement as everything in the frame is accurate to the time. The main challenge on Train Dreams is that Clint likes to work with a lot of freedom for the actors and improvisation. In a period piece, to be 360 degrees and move around, we relied on the amazing sets that Alex made to be able to frame anything we wanted. It allowed us to do something similar to Jockey in the end, in that we had a character and we just followed them. Having a reactive camera works that way, we were just reacting to what Joel was doing.

There’s the big open spaces of the pioneer landscapes, and then a lot of tree cover. How did the light effect the filming?

AV: We tried to embrace and work with the natural light and only manipulate the light by choosing certain times of the day. We shot almost everything in natural light, sometimes with just a bit of enhancement for the fire scenes and the candlelight.

What did you most enjoy about working on this project?

AV: Working with Clint again, and continue to develop and progress what we started with Jockey was very rewarding. I’d happily work with the team again. If Clint wants me to shoot his kids party I’ll do it.

What were you trying to communicate about the film through your design?

Alexandra Schaller: I would call the film a meditation on life and the world, and someone’s interior journey. What’s amazing about this movie is that it’s all outside. So you wouldn’t think there’s much design, but because it’s a period movie the entire world is created. We built so much. A lot of the movie takes place in the woods, it’s about logging old growth trees that don’t exist anymore, so we built some of those huge huge trees. It’s supposed to feel very natural, you’re supposed to feel immersed in that world and feel the power of that and the influence on the main character.

Your recent work on After Yang was much more interiors based, so very different to this film. How do you make sure you always find the points of reference to the characters in such different kinds of sets?

AS: Everything always comes from the character and the story, and I really want these settings to inform that silent storytelling for the audience. In so many movies I’ve worked on it’s about skirting the line between realism and magic, making it feel immersive and believable. Whilst After Yang is set in the future, it still feels very relatable, and I hope that this movie feels the same way. What’s interesting is that both films are time pieces, and neither of them exist anymore.

What was your favourite experience making this film?

AS: Working with Clint and Adolpho and Malgosia was a really wonderful experience. We have a real symbiosis and it makes such a difference to the creative process. I would follow Clint into any world and I’d work with the whole team again in a heartbeat. Malgosia Turzauska and I are very good friends, we met on the set of a movie that also premiered at Sundance, Maggie’s Plan directed by Rebecca Miller. We’ve worked together a few times since then and the collaboration is so good that we try to keep it going. What’s really interesting is that we both read the script for Train Dreams and put together images, and when we shared them we realised they were the same. We found the same colour story for the movie. It’s really incredible to be on the same page from the start.